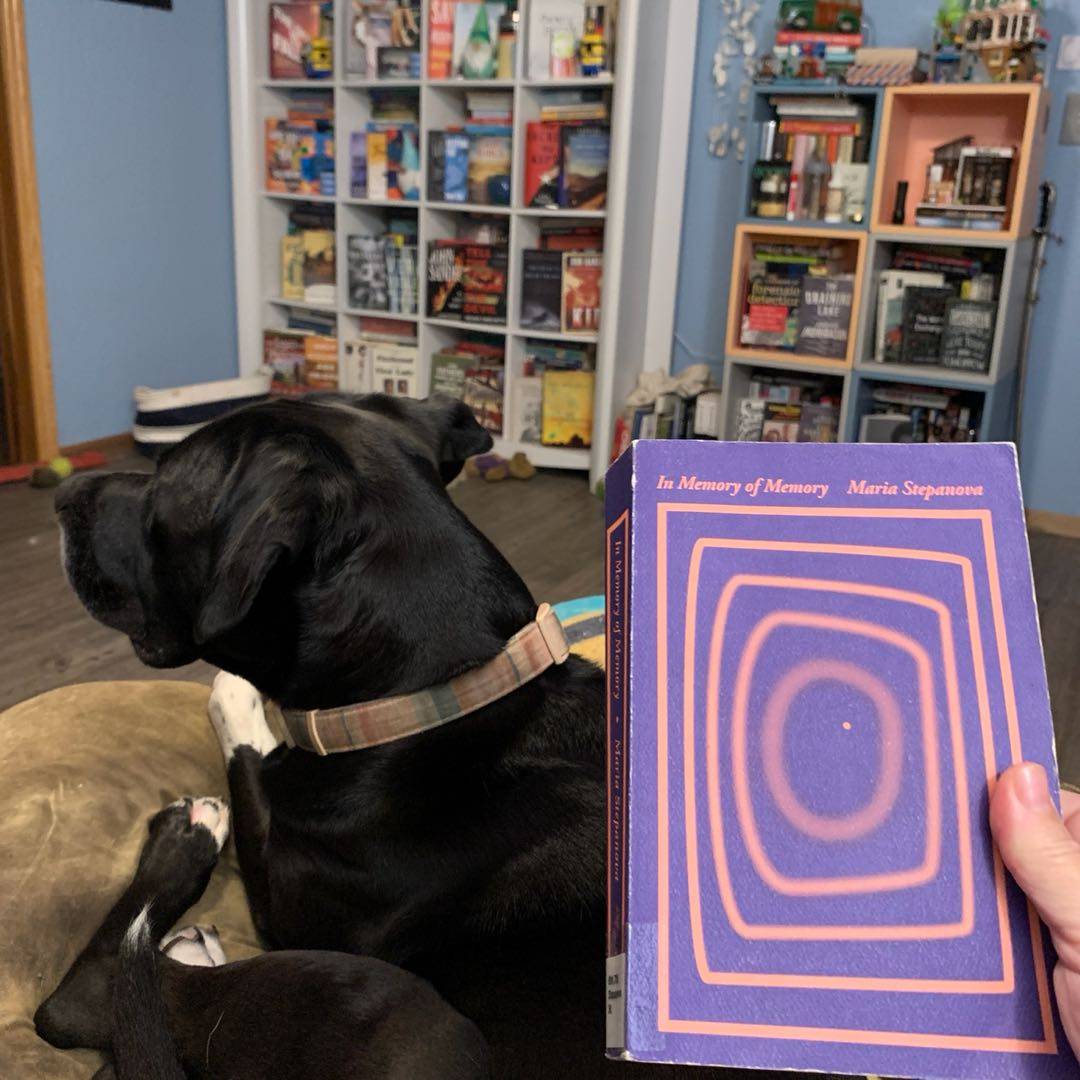

I tried, but I‘m finding this book impenetrable. A Goodreads reviewer saying it has no plot or even characters helped me decide to throw in the towel.

I tried, but I‘m finding this book impenetrable. A Goodreads reviewer saying it has no plot or even characters helped me decide to throw in the towel.

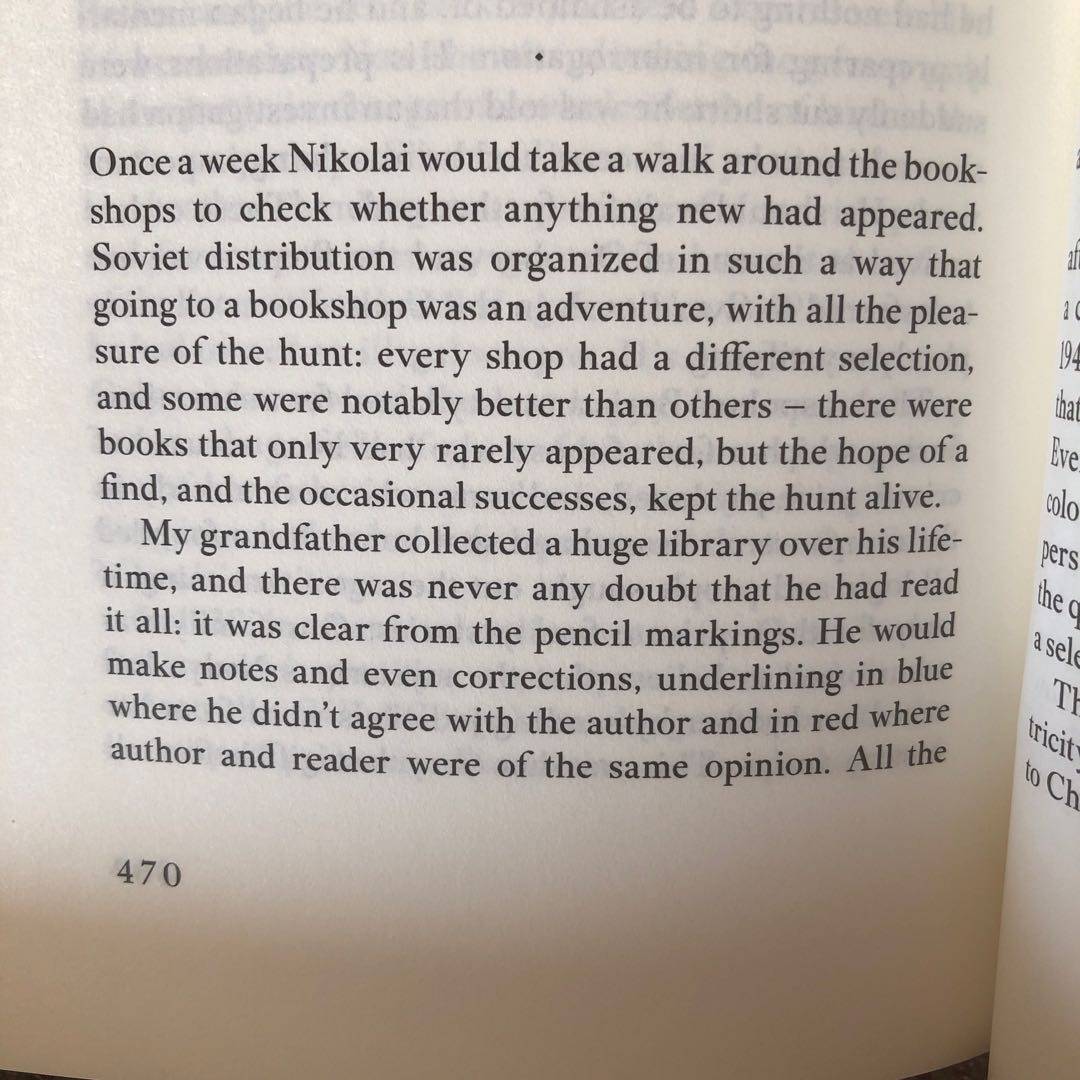

Once a week Nikolai would take a walk around the book shops to check whether anything new had appeared.

Soviet distribution was organized in such a way that going to a bookshop was an adventure, with all the pleasure of the hunt: every shop had a different selection, and some were notably better than others. There were books that only very rarely appeared, but the hope of a find, and the occasional successes, kept the hunt alive.

Amazing book, recommended if you like reflections on how nostalgia and the appeal of family history work. Also a timely reminder of the oppression many Russians have faced within the state.

In April [1911], Lenin began a successful lecture series... on the avenue des Gobelins (another place where my great-grandmother took lodgings). Gorky came to visit him at the end of the month.... In the Jardin du Luxembourg Akhmatova and Modigliani sat on a bench - they couldn't afford to pay for chairs. Each of these people hardly suspected the existence of the others, they were quite alone in the transparent sleeve of their own fate.

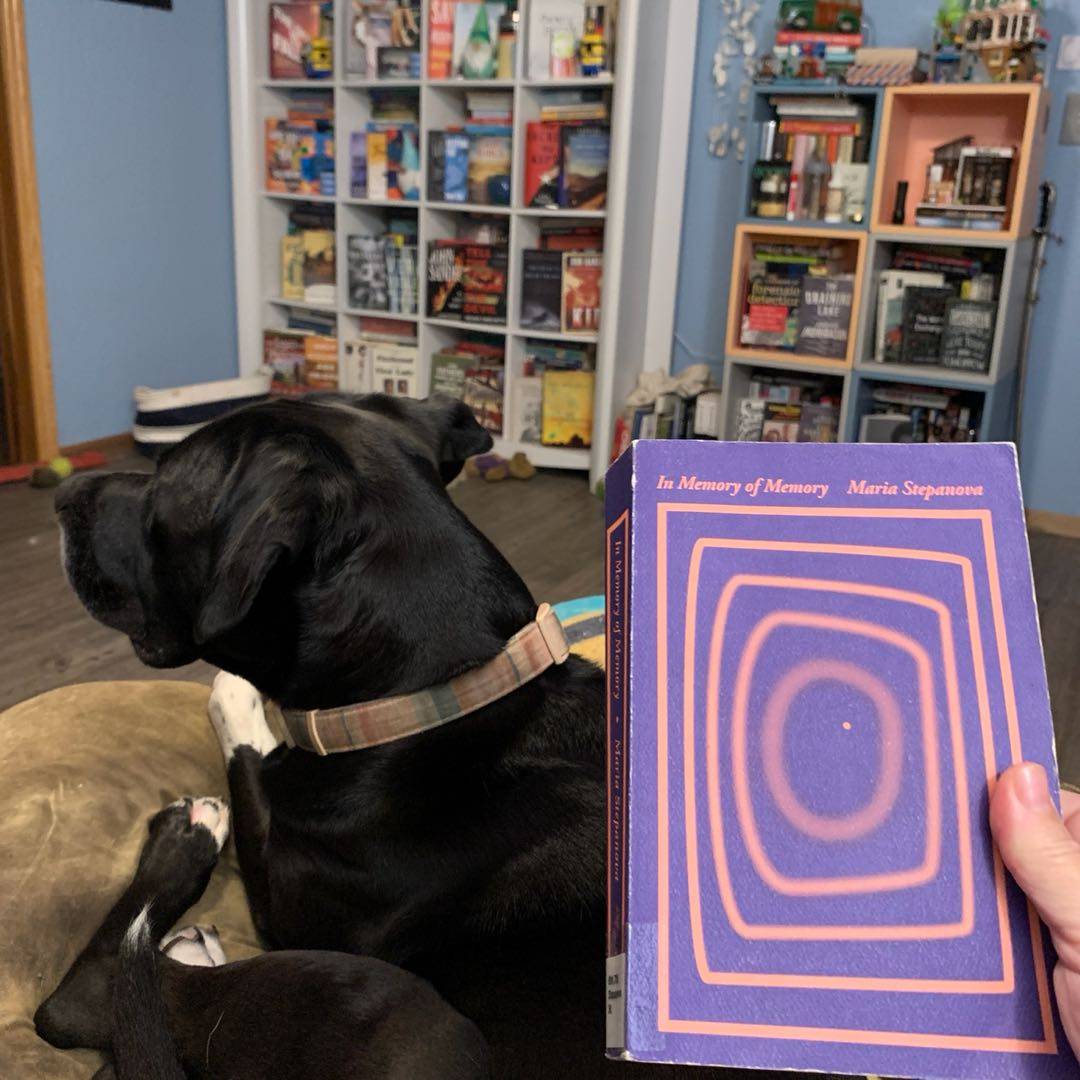

Once when I was ten or a little older, I asked my mother...: What are you most scared of?' I don't know what kind of response I expected, probably 'war'. In Soviet society at the time... [we] lived in the fearful expectation of a third world war; in school we had military training in how to assemble Kalashnikovs and what to do in the event of a nuclear attack (it seemed clear that a machine gun wouldn't help much).

I understood my father's objections to be that his reports on life in Kazakhstan were stylizations of a sort, written to please and entertain his family. What I saw as a picaresque novel, adventures against a colonial back drop, was a memory of dirt, depression and desperate drunkenness for him; of barracks and sheds at the end of the world, swearing soldiers and constant and interminable thievery.

Sometimes it rather seems to me that the pictures [of Holocaust victims] need protecting from us: so that the nakedness of the dying and dead remains their business and illustrates nothing, invokes nothing, serves neither as a basis for conclusions nor identifications after the event. .

Still technology makes its best efforts; it shaves off time's natural build-up of lint - and there are many mansions in its virtual house.

Here‘s a video of me looking back on my reading year, via the challenge constructed by the women of the Reading Women podcast. https://youtu.be/HkC1-Qoyw44

Fortunately, I had already compiled my notes for this before I injured myself.

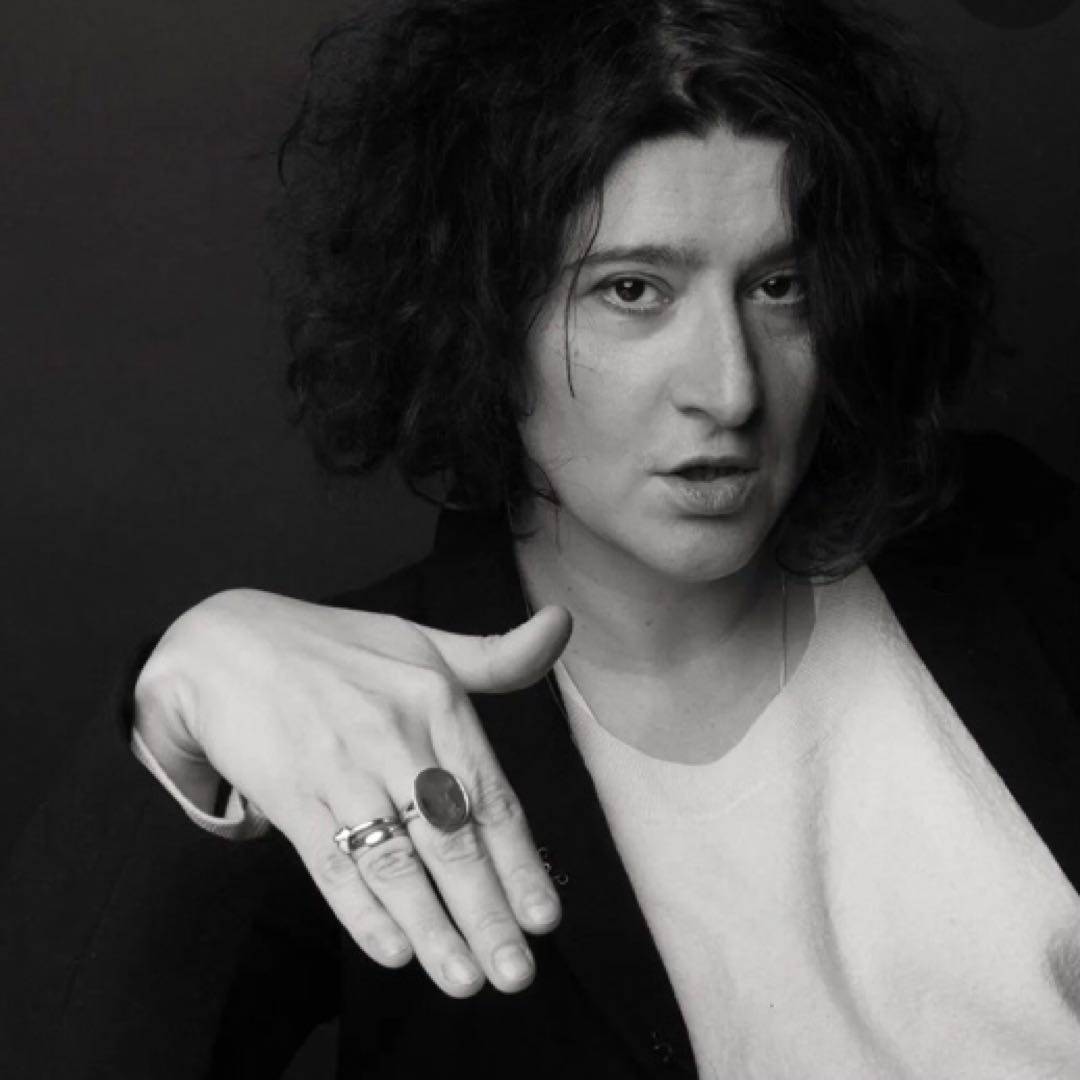

Maria Stepanova said she didn‘t include photos in her book of family history because she didn‘t want to expose her ancestors and relatives to that extent: to connect their stories with images of their faces would be too intimate. There‘s only one photo, and it‘s somewhat blurry, and her grandmother is turning her back to the camera.

Maria Stepanova set out to record her Jewish family‘s history in Russia, but the more she uncovered, the more she doubted what she thought she knew. This remarkable work of literature is hard to classify: it‘s a blend of memoir, fiction, 20th c history, archival documents, & essays about art. These all come gracefully together in what turns out to be a rumination on memory & mortality. Lively & poetic #translation by Sasha Dugdale. #WIT

My china boy seemed to embody the way no story reaches us without having its heels chipped off or its face scratched away.

(Internet photo)

…but we were children of the city who knew the way home from school by the cracks in the pavement, and we had no relationship with the black and granular earth that every spring gave the acacia and the lilac its freedom.

In December 1936 in a New York gallery, Joseph Cornell showed his first film to a small audience. It was called Rose Hobart […]

The 32-year-old Salvador Dalí was in the audience. In the middle of the screening he jumped to his feet and shouted that Cornell had robbed him. He insisted that this idea had been in his subconscious, these had been his, Dalí‘s, dreams, and Cornell had no right to use them as he wished.

(Internet image of Rose Hobart)

This white-hot near-religious belief in higher education was handed down through the generations and I remember it in my own childhood. “We are Jews,” I heard this at the age of seven. You cannot allow yourself the luxury of not having an education.

This book about my family is not about my family at all, but something quite different: the way memory works, and what memory wants from me.

In place of a memory I did not have, an event I did not witness, my memory worked over someone else‘s story; it rehydrated the driest little note and made of it a pop-up cherry orchard.

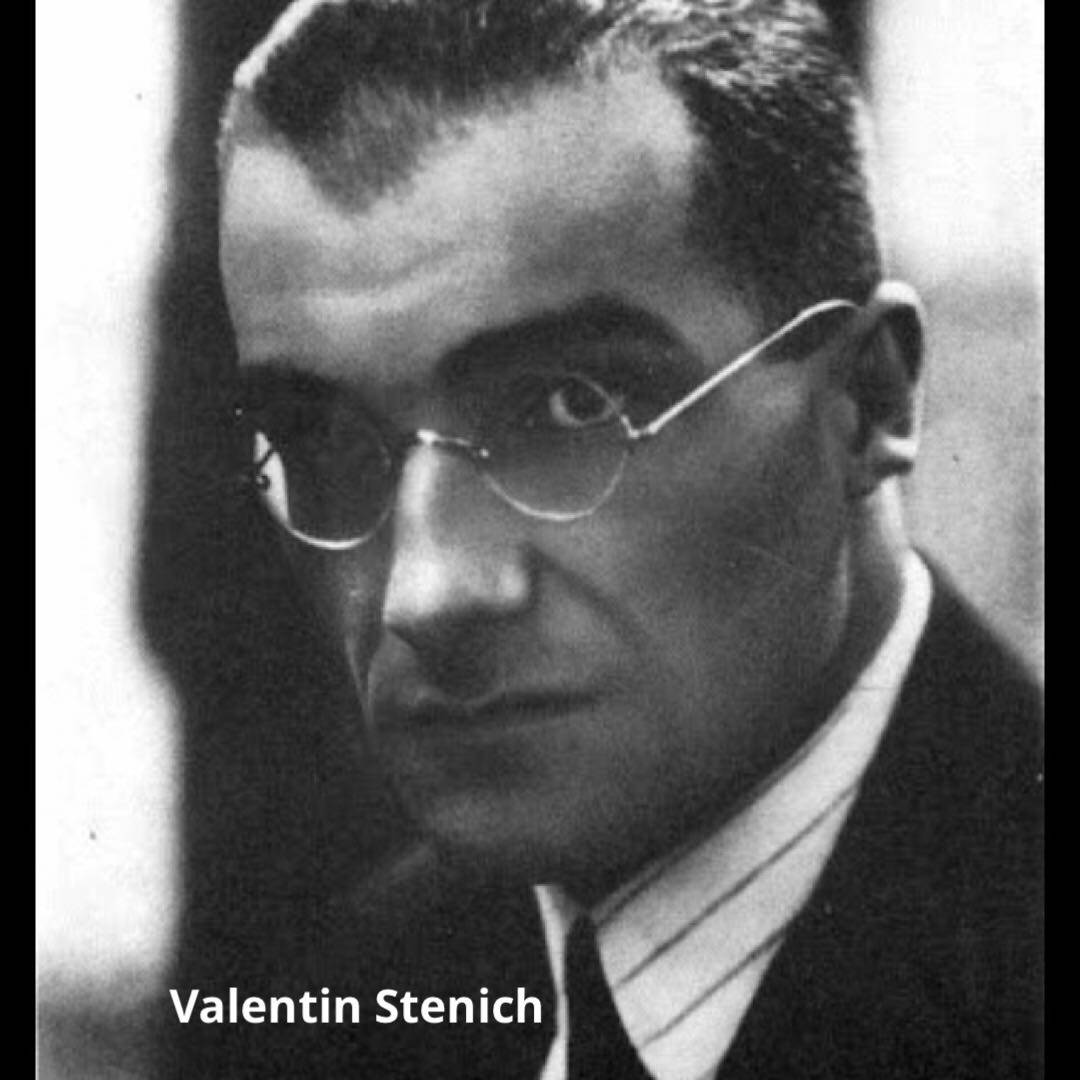

[The poet Valentin Stenich, the first Russian translator of Ulysses] was executed in 1938. It‘s said he did not conduct himself with honour at his interrogations. God forbid anyone should find out how we conduct ourselves at ours.

The painted Rembrandt changes from canvas to canvas, but retains an unchanging presence—almost like the protagonist of a comic or cartoon, Tintin or Betty Boop, whose depictions have become a symbol, a few oversized characteristics grouped around an empty space.

I always knew I would write a book about my family […] because it was simply the case that I was the first and only person in the family who had a reason to speak facing outward, peering out from intimate family conversations as if from under a fur cap, addressing the railway station concourse of collective experience.

(Internet photo)

Maria Stepanova says that in In Memory of Memory (the tagged book), she used some of her own writing from a journal she kept when she was 10 years old.

This book… A book about everything. A book about family history, a book about what we leave behind when we die. A book about authors and artists

The part in the book with the letters written during WWII by a soldier to his family back home - this part will stay with me forever.

She also spends time on authors writing about memory and what we remember, especially Charlotte Solomon‘s “Life? Or Theater?”, and now its on my tbr.

I just love any reference to books and reading in books I read.

I love the idea of every bookstore having a different selection of books.

I finally made it to the end of this heavy, demanding read. More of a long essay than fiction, reflecting on her family‘s past, the history of anti-Semitism, art, and the end of life. It was dark and often difficult to read, but I appreciated it.

Back to the office for me...

I didn't get as much reading done as I wanted to, but hoping the sense of recharge lasts!

No, I‘m not reading the Russian- I needed to see the cover, as she references it in the text. These little dolls were used as packaging material, to preserve/protect larger objects, so you‘re very unlikely to find them in one piece.

And also, this is a strange book. No question, it‘s non-fiction (sorry, International Booker, but it is). It‘s looking at memory, collective, handed-down, post-memory, objects, lists. Very thoughtful- I like it a lot.

Just started reading this for #InternationalBookerPrize2021 - one that I‘ve been putting off. (Why? Am I really that shallow that I‘m put off by Fitzcarraldo covers. Probably. They make the books look so dry 🙁)

Anyhow, this is beautifully written and I think I may just enjoy it. Not one I‘d have picked up on my own...

In the first part, which is more essayistic, the author focuses on memory - what it is, how it works, what encourages them, its significance in the personal history of the individual ... and in the second part she reveals/research hers own family history/memories. The book is nominated for an award in fiction, but IMHO that is a nonfiction work ... unless the jury thinks in the direction that memories are unreliable, a product of imagination 👇

I always bring up my Goodreads TBR list when I‘m wandering around bookstores.

I have 2 copies of In Memory of Memory (tagged book) on order to give as gifts.

Thanks for tagging me!

#two4tuesday

More historiography than novel. Gorgeous prose, the result of Stepanova and a brilliantly able translator in Sasha Dugdale.

What do we do with memories? What function do objects of memory, like photos, serve? Written by a Gen X author with her analog childhood and digital adulthood. She grew up in Russia, her adulthood commenced at the dissolution of the USSR. That history makes this work particularly compelling.

#mariastepanova

#translation

“In the dark days of 1937 the German-Jewish art historian Erwin Panofsky described Piero di Cosimo‘s pictures as the “emotional atavisms” of a “primitive who happened to live in a period of sophisticated civilization.” Rather than a civilized sense of nostalgia, Piero is in the grip of a desperate longing for the disappeared past.”

Image is part of Piero di Cosimo‘s “Forest Fire” painting. 1505 A.D.

“The simplicity and naivety of the past is habitually overstated, and this has gone on for centuries.”

This is a gorgeous book. The breadth of creative artists, writers, and cultural works referenced is astounding. Here‘s a quote about Osip Mandelstam‘s poems written in exile: “They laid no claim to the recent past, nor the palpably accessible present, but tried to cut a large crooked piece out of the future with tailor‘s shears, to run ahead and begin to speak in a universal language which did not yet exist. And they succeeded in this.”

A few interesting things here - the tag book sounds really interesting.

https://bookmarks.reviews/tantalizing-translation-recs-for-2021/

In Memory of Memory | Parable of the Sower

Dictionary

“Riding a bike in Berlin was a new and unfamiliar experience.” -Tagged!

#weekendreads @rachelsbrittain

Aunt Galya, my father‘s sister, died. #FirstLineFridays @ShyBookOwl